In my previous article I provided a sketch of the light detection process in a modern CMOS camera, from photo quants (photons) to digital numbers. We discovered two important physical parameters quantum efficiency qν and camera gain gPC that describe the light detection process in a digital CMOS camera. This monthly notice will focus on how we can evaluate how many photo electrons are detected from the digital numbers in an astronomical picture recorded. Unfortunately, physics and astronomy won't work without mathematics, but computations aren't too hard.

What is unity gain?

Camera gain gPC describes the relation between the number of photo electrons collected and the digital pixel intensity values. In case of a typical scientific or dedicated astronomical camera, whether cooled or not, user control by software provides means to select between arbitrary gain values. Conventional photo cameras provide a knob to select between ISO settings, that define the gain to increase pixel values from a picture taken at low light level conditions. Unity gain denotes the gain setting gPC, where the digital unit of the pixel value is equal, or at least closest to the number of photo electrons freed by photons within the silicon device. Camera gain is simply the quotient of digital numbers divided by the number of electrons counted. If camera gain gPC is smaller than one, then the number of electrons counted are larger than the digital units in the recorded image. If gPC is larger than one, then the digital numbers in our image express to have found more electrons than actually measured.

gPC ≈ 1.

Ideally, camera gain gPC shall be approximately one. This is the unity gain condition.

Evaluation of unity gain

Certain manufacturers of astronomical imaging devices provide information about the gain value, that is closest to the condition. For conventional photo camera ISO settings that reflect unity gain are available from internet databases (see literature section). However, if precise measures are required, the exact gain setting for a specific camera, which is closest to the unity gain condition, shall be evaluated by conducting experiments with different gain settings.

Variance is a mathematical term, that is defined as the mean squared difference of random values and mean value. As already outlined in my previous article, for Poisson distribution the mean value E[X] of the pixel intensities X recorded is the same as their variance Var(X). This can be written as:

E[X] = Var(X)

or rewritten

1 = E[X] / Var(X)

If the photon count is multiplied by an arbitrary factor gPC, mean value and variance of the noisy numbers will not satisfy the above condition. In this case we can compute gPC from the invers quotient of mean value and variance to establish the relation between digital numbers and photo count.

gPC = Var(X) / E[X]

The other way round, we can compute a direct estimate for the electron count from dividing digital numbers in the image by gPC.

To simplify things for further discussion we will check, which gain setting satisfies the above Poisson noise condition, where the quotient of mean value and variance will be closest to one. This can be evaluated by collecting exposures taken from a flat screen at different gain or ISO settings. In astronomy a set of sky flatfield exposures taken at different gain settings is a perfect choice. Under the assumption, neighbouring pixels shall have equal quantum efficiencies, single sky flatfield frames taken at different ISO settings enable a quick evaluation where one shall expect unity gain condition. The assumption is certainly valid for most imaging sensors that provide homogeneous illumination results with no big variation of quantum efficiency across pixels. However, one shall carefully select a homogeneously illuminated pixel area close to the maximum intensity, found with no gradient, which is typically close to the center of the flatfield exposure. Also exclude portions with dust particles or dead pixels that will introduce large scatter of intensities. Finally, we compute mean value E(X) and variance Var(X) of the pixel intensities recorded. Plot values into a graph and see which ISO or gain setting will reflect unity gain the best.

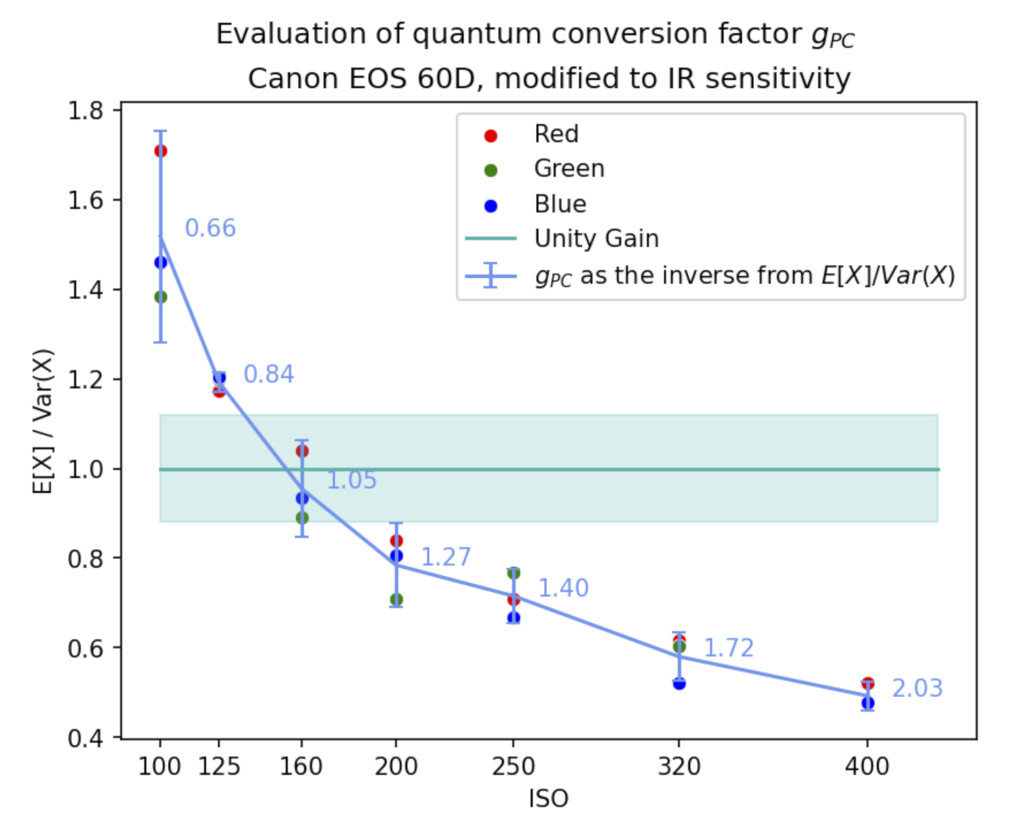

Figure 2: Plot of the quotient E[X]/Var(X) and its inverse quantum conversion factor gPC obtained from pixel intensities that are found in an area of 25x25 pixel of individual sky flatfield frames taken at different ISO settings. A Canon EOS 60D camera was used for this experiment, that has been "astro-modified" by removal of the UV/IR cut filter and diffusor in front of the sensor. Plotted are the measured values for each red, green and blue color channel. Computations take into account, that two green pixel form the digital signal of a Bayer matrix imaging device.

The above plot indicates ISO 160 is closest to satisfy the Poisson noise condition using mean value and variance. This is the point, where unity gain is achieved and the arbitrary gain factor gPC is almost equal to one. If you ever read discussions, if high ISO settings beyond ISO 6400 are nonsense, or not, the plot reveals an interesting result. Settings in the range from ISO 200 onwards to ISO 400 and higher will provide more gain to the signal, but no additional information in terms of having counted more photo electrons. With ISO settings from 200 to 400 digital numbers in the image start to represent a fraction of a single photo electron collected. However, as with any other quantum particle in physics, a photo electron cannot be split or divided into fractions of itself! How could this happen? Additional readout noise will add to the images, which makes noise distribution more broader to smear intensities for high gain or ISO settings. Numbers stored in the digital image at gain values that are too large appear like a fraction of an electron due to noise from the signal amplification within the electronics.

Numbers recorded in a digital image may lie about the true nature and actual count of the quantum particles, i.e. the number of electrons found from the sensor pixel. Gain settings beyond ISO 200 will amplify a noisy number, but will not unveil more light from the noisy signal. In our example, we find unity gain condition close to ISO 160. It shall be mentioned that the above plot taken from a single camera differs from unity gain estimates provided by an internet database. I strongly recommend not to trust any data provided by various internet resources, but calibrate your device by yourself!

Another recommendation to astrophotographers will result: Do not push ISO settings far beyond empty amplification of the signal. In the example ISO 400 of a real Canon camera corresponds to a gain factor where one digital unit represent "half an electron" counted. The consequence of using high gain settings is loss of dynamic range. A digital camera has a limited range of digital numbers. Typically this is 14 bit resolution for modern DSLR cameras with a digital value range between zero and up to a maximum possible digital value of 16383. That means a bright star will run into saturation sooner due to early cut-off from the analog-digital converter. So there exist useless ISO settings, that should be expected earlier, than thought. High ISO settings do not provide an increase of light from the digital pixel intensities.

From the many observations over years, I suggest ISO settings beyond ISO 400 for my DSLR certainly are useless to the observer and shall be avoided in general. The step from ISO 160 towards ISO 400 seems reasonable. However, this already means loss of about one apparent magnitude towards upper intensities of bright stars recorded in the image. High ISO setting will have negative impact on post-processing of crowded stellar fields in astronomical image processing, like photometric analysis or image sharpening techniques. There will be an excuse to go for ISO 400 instead of ISO 160. First, there is an issue with the poor live view of the camera that is not optimal to show very low intensities and see, if a faint astronomical object is properly centered. Second, there exists a trade-off from lower ISO settings. If star detection algorithms start to detect noise peaks instead of stars, then probably ISO settings or exposure time is set too low. Hence, ISO 400 is a good compromise between the trade-off of limiting dynamic range and lowering readout noise. From the various astronomical measures conducted in the past, ISO 400 supports well the ability to conduct precise stellar photometry while decreasing readout noise to a moderate level for this specific Canon camera.

Lesson learned: We should not push ISO settings of any DSLR to high values in astronomy domain. At ISO 160 my Canon camera already operates counting single photons per digital unit. ISO 400 is a reasonable compromise between cut-off of bright stars and low readout noise.

Conclusion and outlook

It might appear like a surprise to the reader: The ability to count individual photo electrons and quantum noise starts early at relatively low ISO setting for a modern DSLR. Readout noise values from a modern CMOS cameras, such as those used in astronomy domain or a modern DSLR, are pretty low in the range of ±1 e- up to only a few electrons per pixel. Natural noise is intrinsic to the light detection process. In a later article, we will see that with exposure times of 30 seconds the resulting photon count and scatter from quantum noise of the illuminated sky, is larger compared to readout noise. Hence, modern CMOS devices operate in the range of counting single photons per digital unit. At this point thinking in quantum counts will provide advantages, like the ability to directly estimate important physical properties of the camera. Thinking in quantum counts easily enabled us to find a proper technique to figure out which ISO setting is optimal to astronomical applications.

[to be continued soon]

Literature

- Planck, M., 1901. On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum. Annalen der Physik. vol.4, p.553

- Bauer, T., Efficient Pixel Binning of Photographs. IADIS International Journal on Computer Science and Information Systems, vol. VI, no. 1, p.1-13, P. Isaías and M. Paprzycki (eds.), 2011. ISSN: 1646-3692

- Photons to photos internet database: https://www.photonstophotos.net/Charts/RN_e.htm