In the 1990ies, I worked as an astronomer at the Hoher List observatory (Germany). My mentor was Prof. E. H. Geyer, an experienced observing astronomer. He created a number of astronomical instruments and measuring devices. From the many fruitful discussions and private lessons I received from him, I remember one special fact, that gained my attraction: Once, he mentioned a specific number of photon events per second that will be recorded from a star of apparent magnitude V=10 when observed with the 1-meter Cassegrain telescope. Although I intuitively got, what he meant, it took me a while to unfold the full scope of this simple sentence. After years, I didn't remember the exact number of photon events he mentioned. Time for recap and research. In this article series we will learn how a digital CMOS camera can be regarded as a photon counting device.

Max Planck's law

Astronomers are interested in energy equivalents. Sometimes, when reading astronomical papers, even for astronomers, it is not even easy to understand measured fluxes from stars, gaseous nebulae and other astronomical targets, that are expressed in multiple different energy equivalents und thus different physical units, that are hard to compare. With the many diverging color bands and filter systems, it will even get harder to compare results (see for example Bessel, 1990). Each ground-based or satellite observatory has its own color filter system invented.

The deduction of the following mathematics is partly taken from one of my previous publications (Bauer, 2011).

Light is an electro-magnetic wave, that is sent from a distant star, for example. Light can also be understood as a particle stream wherever light interacts with material, like a photo-cathode or semiconductor device to detect light. Planck (1901) introduced a formula, that yields a relationship between the photo quantum (photon) energy E, the Planck constant h and the frequency of the light ν:

E = h ν

It is important to understand, light intensities are not measured in arbitrary fractional numbers. Instead, there is a "smallest" piece of quantum energy, the photon, that cannot be split into smaller chunks of energy. This implies consequences how we will be enabled to reveal physical properties of the detector and light source. For example, any incoming flux of the light source will result in a probability distribution to find a number N of particle events within a time frame (second). The detector will not measure a continuous flux value, but any integer number of events per time interval. In a silicon imaging detector photons enter the semi-conductor crystal up to certain depth (transparent depth) where the photon energy may free electrons with certain probability (photo-effect). These free electrons can then be measured as a photo current, amplified and converted into digital numbers. With special photon counting devices photons can be counted individually. In a conventional CMOS device, however, the detection process will not count individual photons, but single electrons are amplified and a photo current is converted into digital numbers. Amplifier noise will add noise to the detected digital signal. Hence, we cannot tell the exact single photon count from digital numbers. The light detection process, on the other side, includes a natural source of noise from the statistical detection process.

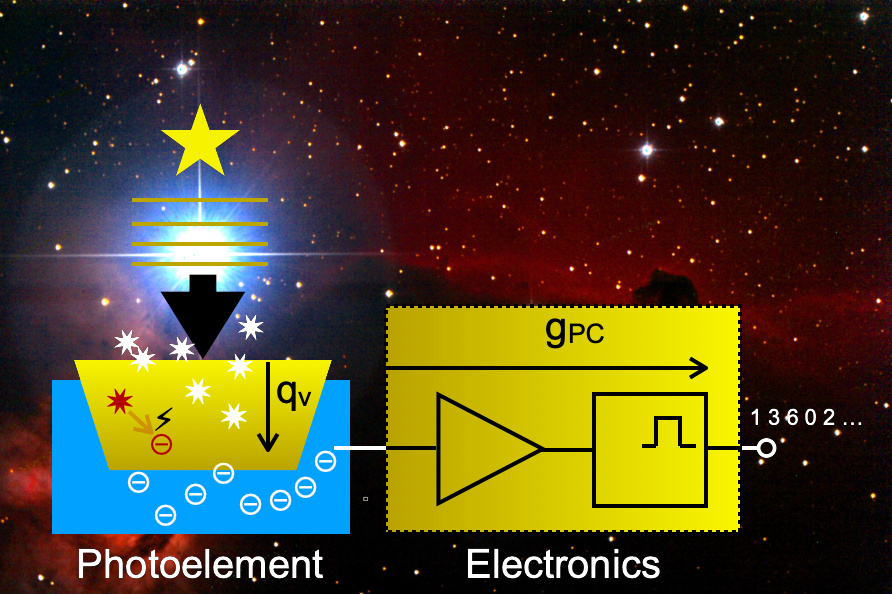

Figure 1: In the conversion process from photo quants (photons) emitted by a star quantum efficiency qν, camera gain gPC and noise from the statistical detection process define the digital numbers counted with each pixel of a modern CMOS or CCD imaging sensor.

Light detection process

A digital image shall be regarded as a set of numbers I(x), which are the measured pixel intensity values at the two-dimensional coordinate x. The incoming flux of light will cause electrons created within the silicon that are collected over time. The pixel intensities I(x,t) therefore are proportional to the flux from the light source at time t. The electron current from the chip is then amplified and digitized by the electronics. This yields certain conversion factor gPC between the actual freed photo electrons and the digital numbers obtained. The relation between the measured photo current NPE(x,t) and the actual number NQ(x,t) of photo events detected is given by a certain quantum efficiency qν. at frequency ν (Mullikin, 1994). Quantum efficiency is driven by the probability to yield a photo electron freed by the energy of a photon. The value of the quantum efficiency is typically less than 1 (100%).

I(x,t) = gPC NPE(x,t) = gPC qν NQ(x,t)

The quantum efficiency depends on the wavelength and thus the energy of the photons. With Planck's concept of the quantum nature of light this translates into:

∑n qν En = E qν NQ(x) ~ NPE(x)

The photo current NPE(x) obtained from the number n of individual photo electrons is proportional to the total energy E of the photo events detected. En is the energy of each individual photo quant collected with index n. In astronomy we typically use color filters, which cover certain wavelength range, like broad blue, green or red color filters of a color camera or dedicated narrow band-pass nebula filters for individual spectral lines. Here, the probability to detect a photo event results from the spectral distribution of light emitted by the star or nebula multiplied by the spectral sensitivity of the optics, detector and filter. Each combination of telescope, filter and camera sensor results in a different quantum efficiency qν, or the overall susceptibility of the optical system, filter and camera.

The individual photon events collected within exposure time do not arrive at constant frequency, but rather follow an irregular process that causes noise to the detection of light. Taking multiple pictures of the same star, the number of photons detected from the star in the different exposures will vary between images. The photon events hitting the sensor at each time interval t of our exposures follow a Poisson distribution. The Poisson distribution is a special case of probability distributions in statistics. It has an interesting property: Given an average number of photons detected, the variance of the number count of events at time intervals tN is the same as the mean value of events counted. The same applies to the collected photo electrons that form the photo current that is converted into digital numbers: With the quantum efficiency as a likelihood to free an electron by an incoming photon, also the number of photo electrons follow a Poisson distribution. From the property of the noise process a condition is found: Mean value and variance (error) of the Poisson distributed values shall be equal. This will enable us to compute conversion factor gPC from noise analysis of the digital numbers.

Conclusion and Outlook

In this article we understood the statistical light detection process. We found a way to compute the number of photon events collected from digital numbers in the image from important properties of the detector: Quantum efficiency qν and the quantum conversion factor gPC.

There is another fundamental consequence of the above computations: The digital numbers recorded reflect a total energy received from the light source. The physical law of energy conservation prohibits any increase of the signal-to-noise level of the digital (astronomical) image recorded in any way by post-processing the immutable digital image (Bauer, 2011). Increase of signal to noise ratio can be done only by collecting more by extending exposure time, increase of telescope aperture, optimization of the optical system, or all together.

The question will remain how to evaluate quantum efficiency qν and conversion factor gPC. The following article will provide a method to evaluate the conversion factor gPC from noise analysis to establish the relationship between photo electron count and digital numbers.

Literature

- Bessell, M. S., 1990. UBVRI Passbands. PASP, 102, 1181.

- Bauer, T., Efficient Pixel Binning of Photographs. IADIS International Journal on Computer Science and Information Systems, vol. VI, no. 1, p.1-13, P. Isaías and M. Paprzycki (eds.), 2011. ISSN: 1646-3692

- Planck, M., 1901. On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum. Annalen der Physik. vol.4, p.553

- Mullikin, J.C. et al, 1994. Methods for CCD Camera Characterization. Proc. SPIE, vol. 2173, 73